Explainer: what is gastroenteritis and why can’t I get rid of it?

The following article, authored by Dr Vincent Ho, School of Medicine Western Sydney University, was originally published with full links on The Conversation.

We’ve all experienced the abdominal cramps and the urge to get to a toilet – quickly! When the stomach and intestinal tract become inflamed, our bodies respond with the sudden onset of diarrhoea, associated nausea and vomiting, abdominal cramping and pain.

Transmissible gastroenteritis is colourfully known as “Montezuma’s revenge”, “Delhi belly”, “stomach flu” and “viral gastro” but let’s use the term “infectious gastroenteritis”.

This includes food poisoning, where bacterial toxins consumed in contaminated food rapidly cause symptoms.

Although infectious gastroenteritis usually resolves on its own, in some cases it can lead to severe consequences, chiefly through dehydration. Worldwide, 1.45 million people die from infectious gastroenteritis each year.

Symptoms can occur as soon as 30 minutes after exposure to the culprit organism or toxin. But most often, symptoms develop 12 to 72 hours after exposure.

Acute infectious gastroenteritis usually resolves within two weeks but severe cases can last several weeks.

Causes

Viruses such as rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus and astrovirus are common causes of infectious gastroenteritis. Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe acute gastroenteritis in infants and young children. Almost every child in the world will suffer at least one infection by the time they are three years old.

Norovirus is the leading cause of gastroenteritis in adults. Norovirus is highly contagious and outbreaks commonly occur in residential care facilities and hospitals. Patients can remain contagious for at least 48 hours after their symptoms have disappeared.

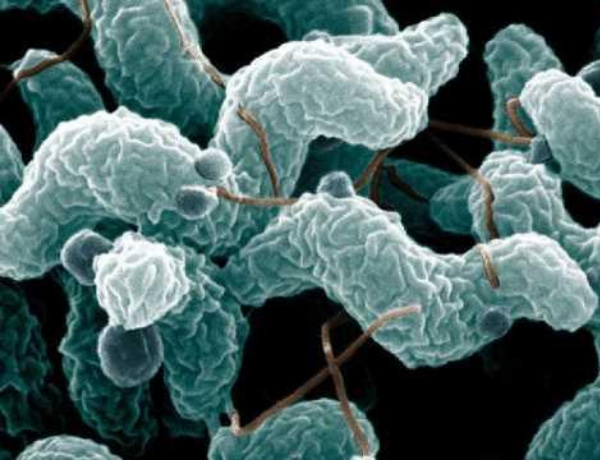

Escherichia coli (e. coli), Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter are common causes of bacterial gastroenteritis. They are often found in contaminated foods including raw or undercooked meat, poultry, seafood and unpasteurised milk.

Bacterial gastroenteritis accounts for 80% of cases of traveller’s diarrhoea and is thought to affect 20% to 50% of international travellers.

Some parasites such as Giardia lamblia, entamoeba histolytica and cryptosporidium are known to cause gastroenteritis. Although usually parasitic gastroenteritis resolves without treatment, people with compromised immune systems can have prolonged symptoms.

Prevention and treatment

The use of clean water and good sanitation practices are important for reducing rates of infectious gastroenteritis. Handwashing with soap has been shown to reduce the risk of gastroenteritis by up to 47%.

Of course, avoiding contaminated foods that could harbour toxic bacteria and parasites is also important.

Vaccinations are also effective, particularly for rotavirus. The rotavirus vaccines have seen a marked decline in the rate and severity of disease in both developing and developed countries.

Oral rehydration is the cornerstone of treatment for those suffering from mild to moderate dehydration. This can be achieved through a solution containing water, salts and sugar. For severe cases of dehydration, hospitalisation and intravenous fluids may be required.

Antibiotics are generally not recommended unless the gastroenteritis is bacterial or parasitic and symptoms are severe.

Longer-term illnesses

What if the symptoms of gastroenteritis still persist months or even years into the future?

Mounting evidence links bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections with an increased risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome. One study followed patients that developed acute gastroenteritis during a large outbreak in 2000. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome at three years was very high at 28.3%. Eight years after the outbreak it was still high at 15.4%.

The intestinal barrier allows key nutrients to enter the gut while maintaining a defence against toxins and noxious organisms. This barrier however can be damaged in acute infectious gastroenteritis. Foreign substances can then enter the deeper tissues of the gut and promote inflammation.

A study examining patients who had gastroenteritis caused by Shigella found that there were increased mast cell numbers in the gut. Mast cells are known to secrete the hormone serotonin which is important for signalling in the enteric nervous system. This then may be another mechanism by which post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome can develop.

Researchers have also studied what happens, at a cellular level, in the gut after acute gastroenteritis. Interstitial cells of Cajal are known as the pacemaker cells of the gut and help digest food and move it through the gut. These cells were altered in mice that were exposed to a type of bacterial gastroenteritis.

Unanswered questions

We have a reasonably good understanding of the causes of infectious gastroenteritis and treatment. But there’s more we need to learn, especially when it comes to understanding how symptoms might persist over the long term.

We are learning to appreciate the significance of a disordered immune system for long-term gastrointestinal symptoms. This opens the possibility for selective use of anti-inflammatory drugs or immune-modifying medications in patients recovering from infectious gastroenteritis.