Health Check: The low-down on ‘worms’ and how to get rid of them

The following article, authored by Dr Vincent Ho, School of Medicine Western Sydney University, was originally published with full links on The Conversation.

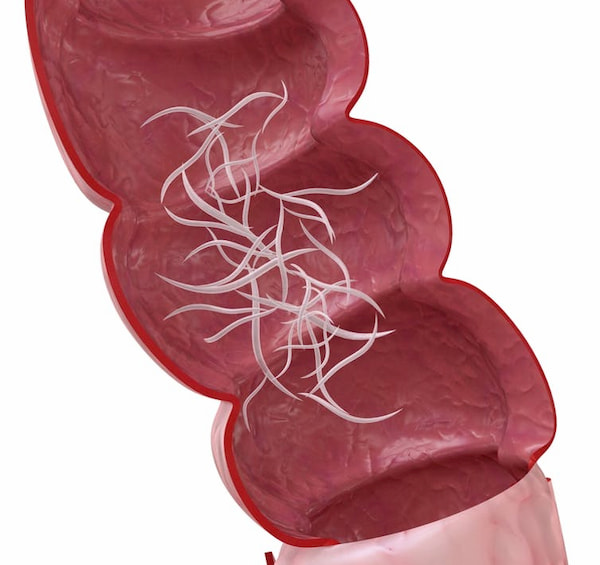

Intestinal worms (or helminths) are multicellular parasites that live inside the gut. When mature, they can generally be seen with the naked eye.

In developing countries with poor sanitation, the most common intestinal worms are transmitted through contaminated soil. The main culprits belong to the roundworm subgroup and include threadworm, large roundworms, whipworms and hookworms.

In Australia, threadworm (or pinworm) is the most common intestinal worm.

These worms hatch out of eggs swallowed by the host. But don’t worry: they’re relatively harmless and easily treated.

Soil-transmitted worms

A large proportion of the world’s population is infected with soil-transmitted worms. The large human roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides, is thought to infect one-sixth of the world’s population. The worm can grow to as long as 35 centimetres.

Soil-transmitted intestinal worms can produce a wide range of symptoms including diarrhoea, abdominal pain, lethargy and weakness.

These infections can cause malnutrition and poor growth. Hookworms and whipworms in particular can cause anaemia, making children feel weak and tired. Some experts believe these worms can also lead to poor performance at school.

Large roundworms, whipworms and hookworms worms are uncommon in urban Australia but rural Indigenous communities have relatively high rates. They’re also seen occasionally in overseas travellers.

Threadworm

Threadworm (Enterobius vermicularis) is very common in Australian children; the prevalence is estimated to be between 10% and 50% in some groups.

Threadworms can grow up to 13 millimetres long and look like small threads of white cotton, hence the name. They attach themselves to the lining of the large intestine. Adult worms can sometimes be seen in feces or eggs may cling to the skin around the anus.

Threadworm infections are often asymptomatic. When symptoms do occur they can include an itchy bottom, particularly at night, reduced appetite and feeling mildly unwell or irritable. In young girls, inflammation can occur around the vagina.

Threadworm can be diagnosed in children using the sticky tape test using a kit from your general practitioner. This test is best done in the morning prior to a bath, as worms can migrate during resting periods.

The test involves separating the buttocks and applying a piece of sticky transparent tape to the area just outside of the anus and between the buttocks. The tape is stuck on the skin, then removed and placed onto a glass slide provided in the kit. The doctor will then examine the slide for worms or worm eggs.

Transmission

Threadworm infection usually occurs by ingesting infectious eggs. Threadworms rely on the itchiness in the anal skin region to transmit their eggs: children tend to scratch their bottom at night and catch the eggs under their fingernails, which they then put in their mouth. So nail biting, poor hygiene or inadequate hand washing contributes to the spread of threadworm.

Children can easily spread the infection to other family members by transferring eggs to bed linen and bathroom fixtures. In the right conditions, eggs can survive for several days.

Humans cannot contract threadworm from animals. But since animals can be carriers of other intestinal worms, it’s a good idea to regularly deworm pets.

Treatment

The most commonly used anti-worm products to treat intestinal worms (threadworms, roundworms and hookworms) are pyrantel, albendazole or mebendazole.

All of these medications are equally effective for threadworm, however albendazole requires a medical prescription.

These anti-worm products only treat the adult threadworms currently residing in the intestines; they don’t treat the eggs or immature worms, which can cause reinfection.

That’s why it’s important to treat the entire family at the same time and to check two weeks after the initial dose in case a second dose of treatment is required.

The role of regular deworming is controversial. Internationally, the World Health Organization recommends annual treatment in areas where soil-transmitted intestinal worms (excluding threadworm) affect 20% to 50% of the population.

But there’s no reason why asymptomatic families in Australia would need regular deworming.